A long time ago I heard that women are not so good at negotiating. You can’t blame this all on women, since part of the problem is how our attempts to negotiate are received.

Recently I was told that young women are “getting *$%^ed” because they are told that the staring salaries at various companies are fixed, which they interpret as “no need to negotiate.” This is far from the truth, because there are moving costs, bonuses, and other possible perks that can be negotiated. If you look at the data and compare what male and female students are getting when they graduate it is not equitable. We need to do a better job mentoring our students how to negotiate.

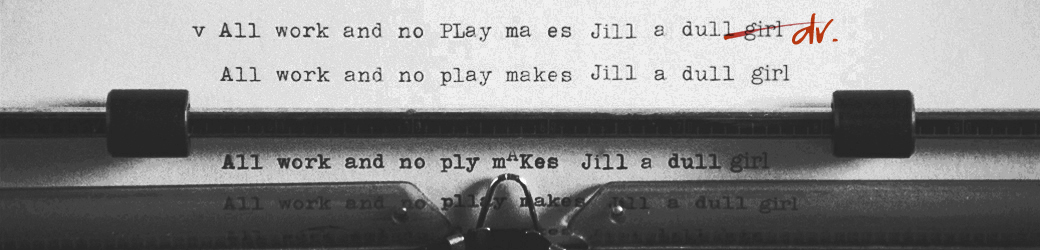

My own experience has led me to conclude that when I negotiate with my pen (through email) I can be far more successful than when I negotiate with my mouth (by talking either in person or on the phone/telecon). Here’s what I have learned in my own negotiations:

- If the promise isn’t in writing it does not exist. Department chairs, Deans and other administrators change (sometimes unexpectedly) and the next person is only obligated to honor things that are in writing (and signed). When you are hired, make sure your needs regarding space, travel, equipment, supplies, student funding, etc. are met as much as possible. It should be in writing how that is going to happen and who is going to pay. Not just that the institution will take care of it, but what funding source at the institution will pick up the bill.

- Negotiate with your pen (keyboard), not your mouth. Unfortunately, when women negotiate with their mouths, people generally respond based on how they look, the tone of their voice and how things went with the last woman who negotiated. When you make your request politely but firmly in writing, you are just stating your needs. The person reading the request can “hear” it in their own inner reading voice. They can respond to the content and take the time to consider what should be a yes and what must be a no.

- The strongest position is one you can walk away from. That’s why having more than one job offer is an advantage. This goes for consulting gigs too. Recently I negotiated a consulting job where I asked for an amount. I was offered about ¼ of the amount. I provided evidence that if I took another job I would be paid ½ again as much as the original amount I asked. I wrote politely that I would prefer to work for them, but only if they could meet my salary and other requests. They met the requests.

- Concisely explain what you will do with the resources you require. If an institution is providing something (money, space, small class enrollment), they deserve to know what the institution will receive in return. This can be phrased as a benefit to the institution, not a defense of your request (even if the request for information seems like a challenge to your request). In my consulting contract negotiation, after the salary was settled, the other party asked for several new things (I’m assuming to get what they thought was their money’s worth). I made a tiny compromise, but basically (in writing) said that what they were requesting would not work and provided the educational reasons. They met my request. Everything went well and I have been asked to perform a second job, but doing much more for the same money. I have made it clear that I will be happy to continue the work, but only under the same conditions as the first job. I also joked (with my mouth) that each time they ask for more, I’ll double my salary request. I can do this because of condition #3 (see above). We’ll see how it goes…

- Be friendly, professional and positive as well as cool and tough. Negotiations are a test of both parties. How will you and the institution behave when things are tough and awkward? Discussions about money often make people act in unusual ways. You can show that you are cool, tough, positive and professional under pressure. Then the institution (and individuals) can expect you to be that way on the job. Your institution deserves that kind of behavior, especially if you are provided the resources you need to do your job well.

- Be reasonable in your expectations. Before the negotiation begins, do your homework (with your mouth). As much as possible, find out from several people what has been done in the past, and what might be possible at that point in time. If you ask for something far outside the normal realm, it can be difficult for administrators to honor your request. If you really need something unusual, then possibly ask (with your mouth since you might not want this in writing) if it would be possible to trade it for something else that others normally receive. Once you have done your homework, you are ready to begin real negotiations.

Pingback: In Negotiations, The Pen Can be Mightier than the Mouth — Tenure, She Wrote | Talmidimblogging

I agree 100%!

Stellar advice! As someone who has, at one time or another ignored just about every point of it, and lived to regret those decisions, I implore everyone – junior faculty and aspiring junior faculty especially – to take every word of it to heart, even if you’re completely convinced that your institution is different, and that you’ll win points as a “team player” by giving ground on these. Young idealists, please understand, the veterans with battle scars aren’t telling you these things because they’re old and cynical, they’re telling you these things because they once were you, and ignoring this advice is how they got the scars.

I wish I had thought of including “how that is going to happen and who is going to pay.” Back when I was hired as a tenure-track faculty member (many years ago) my offer letter, including startup provisions and funds being spelled out, was signed by two administrators- neither of whom were in those positions and/or there by the time I actually arrived some months later. And, let’s just say, the new people in those positions did not feel necessarily responsible to providing things that other people had promised- after all, they hadn’t signed those agreements. (It all worked out okay in the end, but made for a stressful start up period.).

I love this post and as a junior academic I will take all of it to heart.

I am curious about #2. I have zero doubt that this is true (based on my own and others’ personal experiences) but I’m wondering if you know of any studies that back it up? The study that came out a few years ago showing that academics judged men to be more competent than women when shown the exact same CV is one of the studies I circulate to allies to let them know these issues are real/not my imagination/not isolated. It would help to know if there’s a similar body of work out there about women asking for things.